Design for Resilience

The design community is discovering their own complicity in propping up corporate and capitalistic hierarchies that are increasing inequities, maintaining oppressive workplaces, and limiting opportunities for learning, collaboration, autonomy, and creativity.

Solving the problems that we created for ourselves

The dramatic irony facing the design profession is coming to a climax with the realization that we have painted ourselves into a corner. By making our living on being the spokespeople for the leaders of corporate capitalism, we have come to fill the role that is analogous to that of the priests of ancient empires. Priests held the knowledge of the mysteries of cryptic symbol systems and the legacies of meaning hidden in images, symbols and written language. The interpretation of these sacred texts were limited to the literati, a select few who had the time and the resources to expend on learning to read and write and to glean from the wisdom of the ancient sages.

The democratization of literacy, technology, currency and agency have opened the doors to opportunities that could never have existed without the accomplishments of those who came before, and we find ourselves in new, uncharted territory. Yet, we have received an inheritance that threatens our survival. We are discovering that the institutions of education, government, law, business, industry, media, and military are based on centuries-old assumptions and biases that do not lead to human flourishing, but rather an increasing inequality that supports extremes of excess on one hand and oppression on the other. One universal symptom of the trajectory of our global activity as humans has been our tendency to feel less human. By that, I mean that the mental health struggles that we face are pervasive across the spectrum of human experience.

The Role of the Designer

What is the role of a designer, now that the barriers to entry to the profession may be as little as the cost of the computer and the tools and software to perform the work? From the birth of the desktop publishing revolution to the increased access to information afforded by the global adoption of internet-based communications, the knowledge and experience needed to obtain entrance to the design profession is not only much more available but is being actively sought out by a generation that is being taught the value of design thinking. Apple, having now reached the milestone of achieving $1 trillion dollars in market valuation, has proven that design is big business. Everyone wants to be a designer. We have new roles to which people aspire, such as Chief Design Officer.

The world is a very different place than the one where, as a junior high school student, I discovered that there was a path to make money as an artist, in contrast to the stereotypical path of the “starving artist.” Almost 40 years ago, I learned about a profession known as a “Commercial Artist,” and I dedicated myself to learning everything I could. Our high school provided access to equipment for silk screen printing, photo typesetting, a process camera, a photography dark room, a waxer for mechanical paste up, a letterpress printing press, an offset printing press, and the equipment for exposing and developing metal offset printing plates. Still, as far as I was aware, I was the only person in the high school I attended who graduated with the intention to become a “Graphic Designer.”

Now, as children are being taught human-centred design in school, and as UX and UI design have come to be a highly desirable avenue of pursuit for those who would like to be a part of the technological revolution, those of us who have dedicated our lives to the craft of design are left wondering if we are special anymore.

If everyone is special, no one is special.

The Incredibles is a lesson about what makes us special as human beings. The desire to be special can go to such extremes that we can lose our humanity in the process. As we lament our own imposter syndrome, it is interesting to contrast our own foibles with the extremes demonstrated by the villain of the story, Syndrome. In fact, each of the characters is coming to terms with their own experience of agency in the world, or lack of it.

The first one is when Dash gets in trouble in school; on the car ride home, Dash says, “Our powers make us special,” to which Helen (Mrs. Incredible) says, “Everyone is special, Dash”. Dash retorts back to her, “Which is another way of saying that no one is.”

This is not just the opinion of a frustrated little boy, he is parroting the frustrations of his father who later on is arguing that a 4th grade graduation ceremony is silly (in his words, psychotic) because, “They keep celebrating new ways to celebrate mediocrity, but if someone is genuinely exceptional, they shut him down because they don’t want everyone else to feel bad!” And lastly, this theme comes to a head when Syndrome is planning on giving everyone superpowers with his tech and claiming, “When everyone is super, no one will be.”

This movie establishes the fact that there are some people who are exceptional and others who are not. Now, I understand that this is set in a world where some people have superpowers and others do not, but could I say that even in our real world, this is true?

The Modernist Metanarrative

If we look back over the past 100 years since the beginnings of the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany, opened in 1919, we marvel at the accomplishments of painters, artists, and architects to gather and collaborate to fulfill the vision of its founders.

Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist! Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.

Rebuilding out of the ashes of the excesses of the past and the political and economic struggles that culminated in what was then known as The Great War (World War I), these Modernists discarded the forms and models of tradition to create a new, modern approach that combined art and technology with the industrial processes of mass production. As the political unrest of Nazi Germany compelled the students and masters of the Bauhaus to shut down the school, many in the diaspora who were able to escape the violent fate of Europe spread their modernist ideals to schools of art, design, and architecture around the world. Concrete, steel and glass became the modern building materials that would dominate the International Style of architecture, and ultimately the skylines of most major cities.

We credit the work of designers such as Dieter Rams as the influence for the ubiquitous minimalist designs of silicon, aluminum and glass that we use every day in our work and communications.

In spite of their age, Braun products designed by Dieter Rams still look modern and they have been recognised as a source of inspiration by Jonathan Ive, Apple’s Chief Design Officer.

The products that Dieter Rams designed for Braun were a collaboration with the Ulm School of Design, co-founded by a former student of the Bauhaus, Max Bill. Thus, we can draw a line of influence from Walter Gropius, the architect of the Bauhaus, to Dieter Rams at Braun, and to Steve Jobs and Jony Ive at Apple.

Postmodernism

The modern century collapsed along with its modernist ideals and the metanarrative of an artistic and technological utopia with the fall of the World Trade Center. The building embodied a vision of the unity of democracy, technology, capitalism, and globalism that would “one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.” That faith has been in a process of deconstruction ever since, and the postmodern age has yet to determine what, if anything, we should build in its place. The building itself has been replaced, but the core tenets of the faith are in question, and the current political crisis of leadership merely signals the weak foundations of a crumbling nationalist political empire that is quickly being replaced by a global, corporate capitalism, far beyond the constraints of democratic appeals. These hierarchies, representing the largest technology corporations in the world, have assumed dominance over the networks through economic supremacy. As designers, we must take responsibility for the idols we have created in service of big data, key performance indicators, targeted marketing campaigns, and the attention economy. We have learned the language of business, marketing and data science, but have lost our humanity in a Faustian bargain, choosing to focus on present gain without considering the long term consequences. We face a dilemma if we bite the hand that feeds us.

The success of the combustion engine is a case in point. Designers rallied around auto manufacturers to cash in on the design, advertising, and marketing profits of a business that suppressed the more desirable, feasible, and viable electric alternatives to buttress their own supremacy over the market. The success of the automobile promoted urban and suburban development, and economic, political, and military infrastructure that undermines community and destabilizes international diplomatic relationships, creating such a dependence on scarce and depleting resources that we can no longer imagine living without these technological conveniences. Similarly, we are addicted to devices that tend to create lonely, depressed, and anxious people.

Others would go as far to say that social media is ripping society apart.

Can we design our way out of this? Or is design the problem?

Questioning Orthodoxy

Something interesting is happening in religious and spiritual circles that is an interesting analogy of the problems that people are facing in business and politics. Postmodernism is a movement away from the metanarratives of modernism. The term itself is a negation of the previous movement without suggesting an alternative.

Similarly, there is a phenomenon that is referred to as the “nones.” These are the people who would check the box labelled “none” in regard to the question of affiliation to a religious community. What these people have in common is not a rejection of spirituality, necessarily, but a rejection of the hypocrisy of a self-serving religious hierarchy that hypocritically props up the status quo by actively supporting the existing orthodoxies and hierarchical structures while claiming to represent a polemical leader who was known for offering good news for the poor and the oppressed. These religions of fear have been exposed as hollow, since they merely mask the intentions of its leaders and followers to seek their own personal security and prosperity.

The “nones” describe their nomadic search for hope and signs of life as a form of deconstruction. Their teachers describe a process of three phases: construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction. They realize that they have been handed an orthodoxy by the people in the religious communities from which they came that does not actually square with reality. While their view of the world has been constructed through their relationships with these people in their community, they have come to question the very foundations of their beliefs. The are setting out on a journey through the desert by deconstructing inherited dogmas and orthodoxies, and by investigating the latest scholarship and experiments. Then, leaving behind the traditional communities, they are finding relationships, communities, and ways of living that renew their sense of humanity, connection, and belonging. They are reconstructing their personal life, their relationships, and entire communities by reconnecting with people and with the natural world.

In a sense, the design community is discovering their own complicity in propping up corporate and capitalistic hierarchies that are increasing inequities, maintaining oppressive workplaces, and limiting opportunities for learning, collaboration, autonomy, and creativity. They may be personally experiencing the opposite, but the reality for those who are not part of the commercial, technological and creative classes is that they are finding themselves displaced by technologies that provide no alternatives for finding work that can meet basic human needs, let alone work that is meaningful and rewarding.

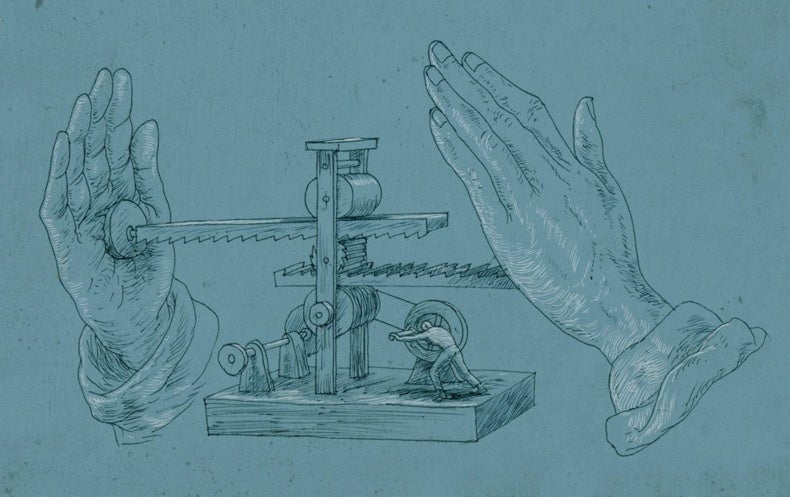

How, then, shall we live, given our growing awareness of the situation in which we find ourselves? We are complicit in a hierarchy that we ourselves have created. To question democracy, capitalism, technology, and globalism is to question the orthodoxies that we have been handed, the very foundations on which design, as a profession, have been established, and that we have been tasked to preserve and herald. The role of the priest is to serve the monarch, maintaining the royal records and histories and disseminating information to the people as deemed appropriate by the monarch and the royal advisors. If we are found to have questions regarding the foundations of the kingdom or empire, we shall lose our role and status, and possibly our heads. We face an existential question, to resist and face the consequences of what we ourselves have wrought, along with the implications of refusing to no longer be complicit in the workings of the machine, or to passively accept our lot in life and carry on.

New Paths

Is the choice so clear cut? There are some who are clearing alternative paths through uncharted territory. The public benefit corporation is one option. Humane technology is another. Social capital is an investment in a mission to harness technology to address core human needs, to drive a bottom-up redistribution of power, capital and opportunity. The blockchain is an attempt to build a trust protocol. Still others are reinterpreting the role of the designer and finding ways to give their work away for free as a way to disrupt the status quo and create new models of impact. A new economy is emerging based on diversity, ecology, and sharing. By observing people and how they interact, we hope to apply what we learn to making cities for people designed for the human scale. The challenge is to create living buildings, alive with human activity designed to integrate harmoniously with the living systems all around us.

Builders Collective

The builders collective is an idea conceived as something akin to a revival of the Bauhaus movement, combining art, design, architecture, theatre, and urban planning. However, the building materials have changed from glass, steel and concrete to perception, cognition, emotion and action, as Jesse James Garrett would express the new context for experience design: design for engagement.

The concept of designing for engagement in combination with the recognition of the unintended consequences of design now leads us toward a movement to realign technology with humanity’s best interests, for humane technology.

What we have in mind is real world experience that combines the concepts of empathy and resilience, to reimagine our social architecture.

Design for resilience starts with the assumption that things will go wrong, and engages in a process of anticipating the unintended consequences (e.g. the internal combustion engine leading to global climate change) through observation (watching, listening) to build empathy, and finds inspiration from nature to solve challenging problems.

The thought, then, is to extend the realm of design from questions of “how" to the deeper questions of “what” and “why.”

For that purpose, we gather as artists, creatives and innovators to build our future on the foundation of senses (perception), minds (cognition), hearts (emotion) and bodies (action) that have been reoriented to the truth about life in our present reality. We are no longer designing the physical artifact, but we are designing the human experience. This is something that cannot be left to governments and corporations, the most inhuman of human inventions. This is a project for humanity as a whole as we envision life as part of an interconnected and interdependent ecosystem on this earth.